From Wikipedia:

2nd President of the United States

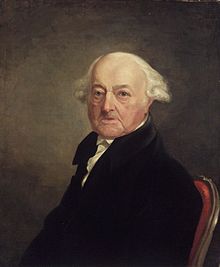

John Adams

2nd President of the United States

John Adams (October 30, 1735 (

O.S. October 19, 1735) – July 4, 1826) was the

second President of the United States (1797–1801), having earlier served as the

first Vice President of the United States. An American

Founding Father, he was a statesman, diplomat, and a leader of American independence from

Great Britain. Well educated, he was an

Enlightenment political theorist who promoted

republicanism.

Adams came to prominence in the early stages of the

American Revolution. A lawyer and public figure in

Boston, as a delegate from

Massachusetts to the

Continental Congress, he played a leading role in persuading Congress to declare independence. He assisted

Thomas Jefferson in drafting the

Declaration of Independence in 1776, and was its primary advocate in the Congress. Later, as a diplomat in Europe, he helped negotiate the eventual

peace treaty with

Great Britain, and was responsible for obtaining vital governmental loans from

Amsterdam bankers.

A political theorist and historian, Adams largely wrote the

Massachusetts Constitution in 1780, which together with his earlier

Thoughts on Government, influenced American political thought. One of his greatest roles was as a judge of character: in 1775, he nominated

George Washington to be

commander-in-chief, and 25 years later nominated

John Marshall to be

Chief Justice of the United States.

Adams' revolutionary credentials secured him two terms as

George Washington's

vice president and his own election in 1796 as the second president.

During his one term, he encountered ferocious attacks by the

Jeffersonian Republicans, as well as the dominant faction in his own

Federalist Party led by his bitter enemy

Alexander Hamilton. Adams signed the controversial

Alien and Sedition Acts, and built up the army and navy especially in the face of an undeclared naval war (called the "

Quasi-War") with

France,

1798–1800. The major accomplishment of his presidency was his peaceful

resolution of the conflict in the face of Hamilton's opposition.

In 1800, Adams was defeated for re-election by Thomas Jefferson and

retired to Massachusetts. He later resumed his friendship with

Jefferson. He and his wife,

Abigail Adams, founded an accomplished family line of politicians, diplomats, and historians now referred to as the

Adams political family. Adams was the father of

John Quincy Adams, the

sixth President of the United States. His achievements have received

greater recognition in modern times, though his contributions were not initially as celebrated as those of other Founders.

Early life

John Adams, the eldest of three sons was born on October 30, 1735 (October 19, 1735 Old Style,

Julian calendar), in what is now

Quincy, Massachusetts (then called the "north precinct" of

Braintree, Massachusetts), to

John Adams, Sr., and

Susanna Boylston Adams.

While he did not speak much of his mother later in life, he commonly praised his father and was very close to him as a child.

Adams' birthplace is now part of

Adams National Historical Park. His father (1691–1761) was a fifth-generation descendant of Henry Adams, who emigrated from

Somerset in England to

Massachusetts Bay Colony in about 1638. The elder Adams was a farmer, a

Congregationalist (that is,

Puritan)

deacon, a lieutenant in the militia and a

selectman,

or town councilman, who supervised schools and roads; Susanna Boylston

Adams was a member of one of the colony's leading medical family, the

Boylstons of

Brookline.

Adams was born to a modest family, but he felt acutely the

responsibility of living up to his family heritage: the founding

generation of Puritans, who came to the American wilderness in the 1630s

and established colonial presence in America. The Puritans of the great

migration "believed they lived in the Bible. England under the

Stuarts was Egypt; they were Israel fleeing ... to establish a refuge for godliness, a city upon a hill."

By the time of John Adams' birth in 1735, Puritan tenets such as

predestination were no longer as widely accepted, and many of their

stricter practices had mellowed with time, but John Adams "considered

them bearers of freedom, a cause that still had a holy urgency." It was a

value system he believed in, and a heroic model he wished to live up

to.

Young Adams went to

Harvard College at age sixteen in 1751. His father expected him to become a minister, but Adams had doubts. After graduating in 1755 with an

A.B., he taught school for a few years in

Worcester,

allowing himself time to think about his career choice. After much

reflection, he decided to become a lawyer, writing his father that he

found among lawyers “noble and gallant achievements" but among the

clergy, the "pretended sanctity of some absolute dunces." He later

became a Unitarian, and dropped belief in predestination, eternal

damnation, the divinity of Christ, and most other Calvinist beliefs of

his Puritan ancestors. Adams then studied law in the office of John

Putnam, the leading lawyer in Worcester.

In 1758, after earning an

A.M. from Harvard,

Adams was admitted to the bar. From an early age, he developed the

habit of writing descriptions of events and impressions of men which are

scattered through his diary. He put the skill to good use as a lawyer,

often recording cases he observed so that he could study and reflect

upon them. His report of the 1761 argument of

James Otis in the

Massachusetts Superior Court as to the legality of

Writs of Assistance is a good example. Otis's argument inspired Adams with zeal for the cause of the American colonies.

On October 25, 1764, five days before his 29th birthday, Adams married

Abigail Smith (1744–1818), his third cousin and the daughter of a

Congregational minister, Rev. William Smith, at

Weymouth, Massachusetts. Their children were

Abigail (1765–1813); future president

John Quincy (1767–1848); Susanna (1768–1770);

Charles (1770–1800);

Thomas Boylston (1772–1832); and Elizabeth (1777).

Adams was not a popular leader like his second cousin,

Samuel Adams. Instead, his influence emerged through his work as a constitutional lawyer and his intense analysis of historical examples, together with his thorough knowledge of the law and his dedication to the principles of

republicanism. Adams often found his inborn contentiousness to be a constraint in his political career.

Career before the Revolution

Opponent of Stamp Act 1765

Adams first rose to prominence as an opponent of the

Stamp Act 1765,

which was imposed by the British Parliament without consulting the

American legislatures. Americans protested vehemently that it violated

their traditional rights as Englishmen. Popular resistance, he later

observed, was sparked by an oft-reprinted sermon of the Boston minister,

Jonathan Mayhew, interpreting

Romans 13 to elucidate the principle of just insurrection.

In 1765, Adams drafted the instructions which were sent by the inhabitants of

Braintree

to its representatives in the Massachusetts legislature, and which

served as a model for other towns to draw up instructions to their

representatives. In August 1765, he anonymously contributed four notable

articles to the

Boston Gazette (republished in

The London Chronicle in 1768 as

True Sentiments of America, also known as

A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law).

In the letter he suggested that there was a connection between the

Protestant ideas that Adams' Puritan ancestors brought to New England

and the ideas behind their resistance to the Stamp Act. In the former he

explained that the opposition of the colonies to the

Stamp Act

was because the Stamp Act deprived the American colonists of two basic

rights guaranteed to all Englishmen, and which all free men deserved:

rights to be taxed only by consent and to be tried only by a jury of

one's peers.

The "

Braintree Instructions"

were a succinct and forthright defense of colonial rights and

liberties, while the Dissertation was an essay in political education.

In December 1765, he delivered a speech before the governor and

council in which he pronounced the Stamp Act invalid on the ground that

Massachusetts, being without representation in Parliament, had not

assented to it.

Boston Massacre

In 1770, a street confrontation resulted in

British soldiers killing five civilians in what became known as the

Boston Massacre.The soldiers involved were arrested on criminal charges. Not

surprisingly, they had trouble finding legal counsel to represent them.

Finally, they asked Adams to defend. He accepted, though he feared it

would hurt his reputation. In their defense, Adams made his now famous

quote regarding making decisions based on the evidence: "Facts are

stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or

the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and

evidence."

Six of the soldiers were acquitted. Two who had fired directly into the

crowd were charged with murder but were convicted only of manslaughter.

Adams was paid eighteen guineas by the British soldiers, or about the

cost of a pair of shoes.

Despite his previous misgivings, Adams was elected to the

Massachusetts General Court (the colonial legislature) in June 1770, while still in preparation for the trial.

Dispute concerning Parliament's authority

In 1772, Massachusetts Governor

Thomas Hutchinson

announced that he and his judges would no longer need their salaries

paid by the Massachusetts legislature, because the Crown would

henceforth assume payment drawn from customs revenues. Boston radicals

protested and asked Adams to explain their objections. In "Two Replies

of the Massachusetts House of Representatives to Governor Hutchinson"

Adams argued that the colonists had never been under the sovereignty of

Parliament. Their original charter was with the person of the king and

their allegiance was only to him. If a workable line could not be drawn

between parliamentary sovereignty and the total independence of the

colonies, he continued, the colonies would have no other choice but to

choose independence.

In

Novanglus; or, A History of the Dispute with America, From Its Origin, in 1754, to the Present Time Adams attacked some essays by

Daniel Leonard that defended Hutchinson's arguments for the absolute authority of Parliament over the colonies. In

Novanglus

Adams gave a point-by-point refutation of Leonard's essays, and then

provided one of the most extensive and learned arguments made by the

colonists against British imperial policy.

It was a systematic attempt by Adams to describe the origins, nature,

and jurisdiction of the unwritten British constitution. Adams used his

wide knowledge of English and colonial legal history to argue that the

provincial legislatures were fully sovereign over their own internal

affairs, and that the colonies were connected to Great Britain only

through the King.

Continental Congress

Massachusetts sent Adams to the first and second

Continental Congresses in 1774 and from 1775 to 1777. In June 1775, with a view of promoting union among the colonies, he nominated

George Washington of Virginia as commander-in-chief of the

army

then assembled around Boston. His influence in Congress was great, and

almost from the beginning, he sought permanent separation from Britain.

Over the next decade, Americans from every state gathered and

deliberated on new governing documents. As radical as it was to write

constitutions (prior tradition suggested that a society's form of

government need not be codified, nor its organic law written down in a

single document), what was equally radical was the revolutionary nature

of American political thought as the summer of 1776 dawned.

Thoughts on Government

Several representatives turned to Adams for advice about framing new

governments. To relieve Adams of the burden of repeatedly writing out

his thoughts,

Richard Henry Lee published one Adams' version, as the pamphlet "

Thoughts on Government" (April 1776), which was subsequently influential in the writing of state constitutions.

Using the conceptual framework of

Republicanism in the United States, the patriots believed it was the corrupt and nefarious aristocrats, in the

British Parliament, and their minions stationed in America, who were guilty of the British assault on American liberty.

Adams advised that the form of government should be chosen to attain

the desired ends, which are the happiness and virtue of the greatest

number of people. With this goal in mind, he wrote in "

Thoughts on Government",

There is no good government but what is republican. That the only valuable part of the

British constitution is so; because the very definition of a republic is an empire of laws, and not of men.

The treatise also defended

bicameralism, for "

a single assembly is liable to all the vices, follies, and frailties of an individual." He also suggested that there should be a

separation of powers between the

executive, the

judicial, and the

legislative branches, and further recommended that if a continental government were to be formed then it "

should sacredly be confined" to certain

enumerated powers. "

Thoughts on Government" was enormously influential and was referenced as an authority in every state-constitution writing hall.

Declaration of Independence

On May 10, 1776 Adams seconded

Richard Henry Lee's resolution calling on the colonies to adopt new (presumably independent) governments.

Adams then drafted a preamble to this resolution which elaborated on

it, and which congress approved on May 15. The full document was, as

Adams put it, "independence itself" and set the stage for the formal passage of the

Declaration of Independence.

Once the combined document passed in May, independence became

inevitable, though it still had to be declared formally. On June 7,

1776, Adams seconded the

resolution of independence introduced by

Richard Henry Lee

which stated, "These colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and

independent states," and championed the resolution until it was adopted

by Congress on July 2, 1776.

He was appointed to a

committee with

Thomas Jefferson,

Benjamin Franklin,

Robert R. Livingston and

Roger Sherman,

to draft the Declaration of Independence, which was to be ready when

congress voted on independence. Because the committee left no minutes,

there is some uncertainty about how the drafting process

proceeded—accounts written many years later by Jefferson and Adams,

although frequently cited, are contradictory and not entirely reliable.

What is certain is that the committee, after discussing the general

outline that the document should follow, decided that Jefferson would

write the first draft.

The committee in general, and Jefferson in particular, thought Adams

should write the document, but Adams persuaded the committee to choose

Jefferson and promised to consult with Jefferson personally.

Although the first draft was written primarily by Jefferson, Adams

continued to occupy the foremost place in the debate on its adoption.

After editing the document further, congress approved it on July 4. Many

years later, Jefferson hailed Adams as "the pillar of [the

Declaration's] support on the floor of Congress, its ablest advocate and

defender against the multifarious assaults it encountered."

After the defeat of the

Continental Army at the

Battle of Long Island on August 27, 1776, Admiral

Lord Richard Howe

requested the Second Continental Congress send representatives in an

attempt to negotiate peace. A delegation including Adams and

Benjamin Franklin met with Howe on

Staten Island on September 11.Both Howe's authority and that of the delegation were limited, and they were unable to find common ground.

When Lord Howe unhappily stated he could only view the American

delegates as British subjects, Adams replied, "Your lordship may

consider me in what light you please, [...] except that of a British

subject."

Lord Howe then addressed the other delegates, stating, "Mr. Adams

appears to be a decided character." Adams learned many years later that

his name was on a list of people specifically excluded from Howe's

pardon-granting authority.

In 1777, Adams began serving as the head of the

Board of War and Ordnance, as well as serving on many other important committees.

In Europe

Congress twice dispatched Adams to represent the fledgling union in

Europe, first in 1777, and again in 1779. He was accompanied, on both

occasions, by his eldest son, John Quincy (who was ten years old at the time of the first voyage).

France

Adams sailed for France aboard the

Continental Navy frigate Boston

on February 15, 1778. The trip through winter storms was treacherous,

with lightning injuring 19 sailors and killing one. Adams' ship was then

pursued by but successfully evaded several British frigates in the

mid-Atlantic. Toward the coast of Spain, Adams himself took up arms to

help capture a heavily armed British merchantman ship, the

Martha. Later, a cannon malfunction killed one and injured five more of Adams' crew before the ship finally arrived in France.

Adams was in some regards an unlikely choice inasmuch as he did not

speak French, the international language of diplomacy at the time.

His first stay in Europe, between April 1, 1778, and June 17, 1779, was

largely unproductive, and he returned to his home in Braintree in early

August 1779.

Between September 1 and October 30, 1779, he drafted the

Massachusetts Constitution together with

Samuel Adams and

James Bowdoin.

He was selected in September 1779 to return to France and, following

the conclusion of the Massachusetts constitutional convention, left on

November 14 aboard the French frigate

Sensible.

On the second trip to Paris, Adams was appointed as

Minister Plenipotentiary

charged with the mission of negotiating a treaty of peace, amity and

commerce with peace commissioners from Britain. The French government,

however, did not approve of Adams' appointment and subsequently, on the

insistence of the French foreign minister, the

Comte de Vergennes,

Benjamin Franklin,

Thomas Jefferson,

John Jay and

Henry Laurens were appointed to cooperate with Adams, although Jefferson did not go to Europe and Laurens was posted to the

Dutch Republic.

In the event Jay, Adams, and Franklin played the major part in the

negotiations. Overruling Franklin and distrustful of Vergennes, Jay and

Adams decided not to consult with France. Instead, they dealt directly

with the British commissioners.

Throughout the negotiations, Adams was especially determined that the

right of the United States to the fisheries along the Atlantic coast

should be recognized. The American negotiators were able to secure a

favorable treaty, which gave Americans ownership of all lands east of

the Mississippi, except

East and

West Florida, which were transferred to Spain. The treaty was signed on November 30, 1782.

Holland

After the peace negotiations began, Adams had spent some time as the

ambassador in the Dutch Republic, then one of the few other Republics in the world (the

Republic of Venice and the

Old Swiss Confederacy

being the other notable ones). In July 1780, he had been authorized to

execute the duties previously assigned to Laurens. With the aid of the

Dutch

Patriot leader

Joan van der Capellen tot den Pol, Adams secured the recognition of the United States as an independent government at

The Hague on April 19, 1782. During this visit, he also negotiated a loan of five million guilders financed by

Nicolaas van Staphorst and

Wilhelm Willink.

In October 1782, he negotiated with the Dutch a treaty of amity and

commerce, the first such treaty between the United States and a foreign

power following the 1778 treaty with France. The house that Adams bought

during this stay in

The Netherlands became the first American-owned embassy on foreign soil anywhere in the world. For two months during 1783, Adams lodged in London with radical publisher

John Stockdale.

In 1784 and 1785, he was one of the architects of far-going trade relations between the

United States and

Prussia. The Prussian ambassador in The Hague,

Friedrich Wilhelm von Thulemeyer, was involved, as were Jefferson and Franklin, who were in Paris.

Britain

In 1785, John Adams was appointed the first American minister to the

Court of St. James's (ambassador to

Great Britain).

In his diary he mentions an exchange between himself and another

ambassador who asked if he had often been in England and if he had

English relations to which Adams explained he had only been to England

once for a two month visit back in 1783 and that he had no relations in

the country. The ambassador asked "None, how can that be? you are of

English extraction?" to which Adams replied "Neither my father or

mother, grandfather or grandmother, great grandfather or great

grandmother, nor any other relation that I know of, or care a farthing

for, has been in England these one hundred and fifty years; so that you

see I have not one drop of blood in my veins but what is American".

When he was presented to his former sovereign,

George III,

the King intimated that he was aware of Adams' lack of confidence in

the French government. Adams admitted this, stating: "I must avow to

your Majesty that I have no attachment but to my own country."

Queen Elizabeth II of the

United Kingdom referred to this episode on July 7, 1976, at the

White House. She said:

John Adams, America's first ambassador, said to my ancestor, King

George III, that it was his desire to help with the restoration of "the

old good nature and the old good humor between our peoples." That

restoration has long been made, and the links of language, tradition,

and personal contact have maintained it.

While in London, John and Abigail had to suffer the stares and

hostility of the Court, and chose to escape it when they could by

seeking out

Richard Price, minister of

Newington Green Unitarian Church and instigator of the

Revolution Controversy. Both admired Price very much, and Abigail took to heart the teachings of the man and his protegee

Mary Wollstonecraft, author of

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Adams' home in England, a house off London's

Grosvenor Square,

still stands and is commemorated by a plaque. He returned to the United

States in 1788 to continue his domestic political life.

Constitutional ideas

Massachusetts's new constitution,

ratified in 1780 and written largely by Adams himself, structured its

government most closely on his views of politics and society.

It was the first constitution written by a special committee and

ratified by the people. It was also the first to feature a bicameral

legislature, a clear and distinct executive with a partial (two-thirds)

veto (although he was restrained by an executive council), and a

distinct judicial branch.

While in London, Adams published a work entitled

A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States (1787).In it he repudiated the views of

Turgot

and other European writers as to the viciousness of the framework of

state governments. Turgot argued that countries that lacked

aristocracies needn't have bicameral legislatures. He thought that

republican governments feature "all authorities into one center, that of

the nation."

In the book, Adams suggested that "the rich, the well-born and the

able" should be set apart from other men in a senate—that would prevent

them from dominating the lower house. Wood (2006) has maintained that

Adams had become intellectually irrelevant by the time the Federal

Constitution was ratified. By then, American political thought,

transformed by more than a decade of vigorous and searching debate as

well as shaping experiential pressures, had abandoned the classical

conception of politics which understood government as a mirror of social

estates.

Americans' new conception of

popular sovereignty

now saw the people-at-large as the sole possessors of power in the

realm. All agents of the government enjoyed mere portions of the

people's power and only for a limited time. Adams had completely missed

this concept and revealed his continued attachment to the older version

of politics.Yet Wood overlooks Adams' peculiar definition of the term "republic,"

and his support for a constitution ratified by the people.

He also underplays Adams' belief in checks and balances. "Power must be

opposed to power, and interest to interest," Adams wrote; this

sentiment would later be echoed by

James Madison's famous statement that "[a]mbition must be made to counteract ambition" in

The Federalist No. 51, in explaining the powers of the branches of the

United States federal government under the new

Constitution. Adams did as much as anyone to put the idea of "checks and balances" on the intellectual map.

Adams'

Defence can be read as an articulation of the

classical republican theory of

mixed government.

Adams contended that social classes exist in every political society,

and that a good government must accept that reality. For centuries,

dating back to Aristotle, a mixed regime balancing monarchy,

aristocracy, and democracy—that is, the king, the nobles, and the

people—was required to preserve order and liberty.

Adams never bought a slave and declined on principle to employ slave labor.

Abigail Adams opposed slavery and employed free blacks in preference to

her father's two domestic slaves. John Adams spoke out in 1777 against a

bill to emancipate slaves in Massachusetts, saying that the issue was

presently too divisive, and so the legislation should "sleep for a

time." He also was against use of black soldiers in the Revolution, due to opposition from southerners.

Adams generally tried to keep the issue out of national politics, because of the anticipated southern response.Though it is difficult to pinpoint the exact date on which slavery was

abolished in Massachusetts, a common view is that it was abolished no

later than 1780, when it was forbidden by implication in the Declaration

of Rights that John Adams wrote into the Massachusetts Constitution.

Vice Presidency

While Washington won the

presidential election of 1789 with 69 votes in the

electoral college, Adams came in second with 34 votes and became Vice President. According to

David McCullough, what he really might have wanted was to be the first

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

He presided over the Senate but otherwise played a minor role in the

politics of the early 1790s; he was reelected Vice President in

1792. Washington seldom asked Adams for input on policy and legal issues during his tenure as vice president.

In the first year of Washington's administration, Adams became deeply

involved in a month-long Senate controversy over the official title of

the President. Adams favored grandiose titles such as "His Majesty the

President" or "His High Mightiness" over the simple "President of the

United States" that eventually won the debate. The pomposity of his

stance, along with his being overweight, led to Adams earning the

nickname "His Rotundity."

As

president of the Senate, Adams cast 29

tie-breaking votes—a record that only

John C. Calhoun came close to tying, with 28.

His votes protected the president's sole authority over the removal of

appointees and influenced the location of the national capital. On at

least one occasion, he persuaded senators to vote against legislation

that he opposed, and he frequently lectured the Senate on procedural and

policy matters. Adams' political views and his active role in the

Senate made him a natural target for critics of the

Washington

administration. Toward the end of his first term, as a result of a

threatened resolution that would have silenced him except for procedural

and policy matters, he began to exercise more restraint. When the two

political parties formed, he joined the

Federalist Party, but never got on well with its dominant leader

Alexander Hamilton. Because of Adams' seniority and the need for a northern president, he was elected as the Federalist nominee for president in

1796, over

Thomas Jefferson, the leader of the opposition

Democratic-Republican Party. His success was due to peace and prosperity; Washington and Hamilton had averted war with Britain with the

Jay Treaty of 1795.

Adams' two terms as Vice President were frustrating experiences for a

man of his vigor, intellect, and vanity. He complained to his wife

Abigail, "My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most

insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his

imagination conceived."

Election of 1796

The 1796 election was the first contested election under the

First Party System. Adams was the presidential candidate of the

Federalist Party and

Thomas Pinckney, the

Governor of

South Carolina,

was also running as a Federalist (at this point, the vice president was

whoever came in second, so no running mates existed in the modern

sense). The Federalists wanted Adams as their presidential candidate to

crush Thomas Jefferson's bid. Most Federalists would have preferred

Hamilton to be a candidate. Although Hamilton and his followers

supported Adams, they also held a grudge against him. They did consider

him to be the lesser of the two evils. However, they thought Adams

lacked the seriousness and popularity that had caused Washington to be

successful and feared that Adams was too vain, opinionated,

unpredictable, and stubborn to follow their directions.

Adams' opponents were former

Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson of

Virginia, who was joined by

Senator Aaron Burr of

New York on the

Democratic-Republican ticket.

As was customary, Adams stayed in his home town of

Quincy rather than actively campaign for the Presidency. He wanted to stay out of what he called the silly and wicked game. His

party, however, campaigned for him, while the

Democratic-Republicans campaigned for Jefferson.

It was expected that Adams would dominate the votes in New England,

while Jefferson was expected to win in the Southern states. In the end,

Adams won the election by a narrow margin of 71 electoral votes to 68

for Jefferson (who became the vice president).

Presidency: 1797–1801

As President, Adams followed Washington's lead in making the presidency the example of republican values, and stressing

civic virtue;

he was never implicated in any scandal. Adams continued not just the

Washington cabinet but all the major programs of the Washington

Administration as well. Adams continued to strengthen the central

government, in particular by expanding the navy and army. His economic

programs were a continuation of those of Hamilton, who regularly

consulted with key cabinet members, especially the powerful Secretary of

the Treasury,

Oliver Wolcott, Jr.

Historians debate his decision to keep the Washington cabinet. Though

they were very close to Hamilton, their retention ensured a smoother

succession.

He remained quite independent of his cabinet throughout his term, often

making decisions despite strong opposition from it. It was out of this

management style that he avoided war with France, despite a strong

desire among his cabinet secretaries for war. The

Quasi-War with France resulted in the

disentanglement with European affairs that Washington had sought. It also, like

other conflicts, had enormous psychological benefits, as America saw itself as holding its own against a European power.

Historian George Herring argues that Adams was the most independent-minded of all the founders.

Though he aligned with the Federalists, he was more his own party,

disagreeing with the Federalists almost as much as he did the

Democratic-Republican opposition.

Though often described as "prickly", his independence meant that he had

a talent for making good decisions in the face of almost universal

hostility. Indeed, it was Adams' decision to push for peace with France, rather than to continue hostilities, that hurt his popularity.

Though this decision played an important role in his reelection defeat,

he was ultimately thrilled with that decision, so much so that he had

it engraved on his tombstone.

Adams spent much of his term at his home in Massachusetts, ignoring the

details of political patronage that were not ignored by others. Adams'

combative spirit did not always lend itself to presidential decorum, as

Adams himself admitted in his old age: "[As president] I refused to

suffer in silence. I sighed, sobbed, and groaned, and sometimes

screeched and screamed. And I must confess to my shame and sorrow that I

sometimes swore."

Quasi-War and peace with France

John Adams said, in a letter to James Lloyd, January 1815, of peace:

"I desire no other inscription over my gravestone than: Here lies

John Adams, who took upon himself the responsibility of the peace with

France in the year 1800."

Adams' term was marked by intense disputes over foreign policy, in particular a desire to stay out of the

expanding conflict in Europe.

Britain and France were at war; Hamilton and the Federalists favored Britain, while Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans favored France.

The French wanted Jefferson to be elected president, and when he wasn't, they became even more belligerent. When Adams

entered office,

he realized that he needed to continue Washington's policy of staying

out of the European war. Indeed, the intense battle over the

Jay Treaty in 1795 permanently polarized politics up and down the nation, marking the start of the

First Party System.

The French saw America as Britain's junior partner and began seizing

American merchant ships that were trading with the British. Americans

remained pro-French, due to France's assistance during the

Revolutionary War. Because of this, Americans wouldn't rally behind Adams, nor anyone else, to stop France.

That problem ended with the

XYZ Affair,

in which the French demanded huge bribes before any discussions could

begin. Before this event, Americans mostly supported France, but after

the event, most opposed France. The Jeffersonians, who were friends to

France, were embarrassed and quickly became the minority as Americans

began to demand full scale war. Adams and his advisers knew that America

would be unable to win such a conflict, as France at the time was

successfully fighting much of Europe. Instead, Adams pursued a strategy

whereby American ships would harass French ships in an effort to stop

the French assaults on American interests. This was the undeclared naval

war between the U.S. and France, called the

Quasi-War,

which broke out in 1798.

There was danger of invasion from the much

larger and more powerful French forces, so Adams and the Federalist

congress built up the

army,

bringing back Washington at its head. Washington wanted Hamilton to be

his second-in-command and, given Washington's fame, Adams reluctantly

gave in. Given Washington's age, as everyone knew, Hamilton was truly in charge. Adams rebuilt the Navy, adding

six fast, powerful frigates, most notably the

USS Constitution. To pay for the new Army and Navy, Congress imposed new taxes on property: the Direct Tax of 1798.

It was the first (and last) such federal tax. Taxpayers were angry,

nowhere more so than in southeast Pennsylvania, where the bloodless

Fries's Rebellion

broke out among rural German-speaking farmers who protested what they

saw as a threat to their republican liberties and to their churches.

Hamilton assumed a high degree of control over the War department,

and the rift between Adams and Hamilton's supporters grew wider. They

acted as though Hamilton were president by demanding that he control the

army. They also refused to recognize the necessity of giving prominent

Democratic-Republicans positions in the army, which Adams wanted to do

in order to gain Democratic-Republican support. By building a large

standing army,

Hamilton's supporters raised popular alarms and played into the hands

of the Democratic-Republicans. They also alienated Adams and his large

personal following. They shortsightedly viewed the Federalist party as

their own tool and ignored the need to pull together the entire nation

in the face of war with France.

Overall, however, due to patriotism and a series of naval victories,

the war remained popular and Adams' popularity remained high.

Adams knew victory in an all out war against imperial France would be

impossible, so despite the threats to his popularity, he sought peace.

In February 1799, he stunned the country by sending diplomat

William Vans Murray on a peace mission to France.

Napoleon, realizing that the conflict was pointless, signaled his readiness for friendly relations. At the

Convention of 1800 the

Treaty of Alliance of 1778

was superseded and the United States could now be free of foreign

entanglements, as Washington advised in his farewell address. He brought

in

John Marshall as Secretary of State and demobilized the emergency army.

Adams avoided war, but deeply split his own party in the process. As he

suspected would happen, peace hurt his popularity. Nevertheless, Adams

was extremely proud of having kept the nation out of war; later in life

he even asked that his tombstone read "Here lies John Adams, who took

upon himself the responsibility of Peace with France in the year 1800."

Alien and Sedition Acts

Though the Democratic-Republicans were discredited by the

XYZ Affair, their opposition to the Federalists remained high. In an environment of war, and with recent memories of the

reign of terror during the

French Revolution,

nerves remained explosive. Democratic-Republicans had supported France,

and some even seemed to want an event similar to the French Revolution

to come to America to overthrow the Federalists.

When Democratic-Republicans in some states refused to enforce federal

laws, and even threatened possible rebellion, some Federalists

threatened to send in an army and force them to capitulate.

As the paranoia sweeping Europe was bleeding over into America, calls

for secession reached unparalleled heights, and America seemed ready to

rip itself apart.

Some of this was seen by Federalists as having been caused by French

and French-sympathizing immigrants. Federalists in Congress therefore

passed the

Alien and Sedition Acts, which were signed by Adams in 1798.

There were four separate acts, the

Naturalization Act,

the Alien Act, the Alien Enemies Act, and the Sedition Act. These four

acts were passed to cool down the opposition by stopping their most

extreme firebrands. The Naturalization Act changed the period of

residence required before an immigrant could attain American citizenship

to 14 years (naturalized citizens tended to vote for the

Democratic-Republicans). The Alien Friends Act and the Alien Enemies Act

allowed the president to deport any foreigner he thought dangerous to

the country. The Sedition Act made it a crime to publish "false,

scandalous, and malicious writing" against the government or its

officials. Punishments included 2–5 years in prison and fines of up to

$5,000. Although Adams had not originated or promoted any of these acts,

he nevertheless signed them into law.

Those acts, and the high-profile prosecution of a number of newspaper

editors and one member of Congress by the Federalists, became highly

controversial. Some historians have noted that the Alien and Sedition

Acts were relatively rarely enforced, as only 10 convictions under the

Sedition Act have been identified and as Adams never signed a

deportation order, and that the furor over the Alien and Sedition Acts

was mainly stirred up by the Democratic-Republicans. However, other

historians emphasize that the Acts were highly controversial from the

outset, resulting in many aliens leaving the country voluntarily, and

created an atmosphere where opposing the Federalists, even on the floor

of Congress, could and did result in prosecution. The election of 1800

became a bitter and volatile battle, with each side expressing

extraordinary fear of the other party and its policies. After Democratic-Republicans won in 1800, they used the acts against Federalists before the acts finally expired.

Reelection campaign 1800

The death of Washington, in 1799, weakened the Federalists, as they

lost the one man who symbolized and united the party. In the

presidential election of 1800, Adams and his fellow Federalist candidate,

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney,

went against the Republican duo of Jefferson and Burr. Hamilton tried

his hardest to sabotage Adams' campaign in the hope of boosting

Pinckney's chances of winning the presidency. In the end, Adams lost

narrowly to Jefferson by 65 to 73 electoral votes, with New York casting

the decisive vote.

Adams was defeated because of better organization by the Republicans

and Federalist disunity; by the controversy of the Alien and Sedition

Acts, the popularity of Jefferson in the south, and the effective

politicking of

Aaron Burr in

New York State,

where the legislature (which selected the electoral college) shifted

from Federalist to Democratic-Republican on the basis of a few wards in

New York City controlled by Burr's machine.

Ultimately, however, Jefferson owed his election victory to the South's

inflated number of Electors, which counted slaves under the

three-fifths compromise.

In the closing months of his term Adams became the first president to occupy the new, but unfinished

President's Mansion (later known as the White House), beginning November 1, 1800.

Midnight Judges

The lame-duck session of Congress enacted the Judiciary Act of 1801,

which created a set of federal appeals courts between the district

courts and the Supreme Court. The purpose of the statute was

twofold—first, to remedy the defects in the federal judicial system

inherent in the

Judiciary Act of 1789,

and, second, to enable the defeated Federalists to staff the new

judicial offices with loyal Federalists in the face of the party's

defeat in presidential and congressional elections in 1800.

As his term was expiring, Adams filled the vacancies created by this

statute by appointing a series of judges, whom his opponents called the "

Midnight Judges"

because most of them were formally appointed days before the

presidential term expired. Most of these judges lost their posts when

the Jeffersonian Republicans enacted the Judiciary Act of 1802,

abolishing the courts created by the Judiciary Act of 1801 and returning

the structure of the federal courts to its original structure as

specified in the 1789 statute.

One of Adams' greatest legacies was his

naming of

John Marshall as the fourth

Chief Justice of the United States to succeed

Oliver Ellsworth,

who had retired due to ill health. Marshall's long tenure represents

the most lasting influence of the Federalists, as Marshall infused the

Constitution with a judicious and carefully reasoned nationalistic

interpretation and established the Judicial Branch as the equal of the

Executive and Legislative branches.

After his presidency

Following his 1800 defeat, Adams retired into private life. Depressed

when he left office, he did not attend Jefferson's inauguration, making

him one of only four surviving presidents (i.e., those who did not die

in office) not to attend his successor's inauguration. Interestingly,

one of the other three was his son,

John Quincy Adams.

Adams' correspondence with Jefferson at the time of the transition

suggests that he did not feel the animosity or resentment that later

scholars have attributed to him. He left Washington before Jefferson's

inauguration as much out of sorrow at the death of his son Charles Adams

(due in part to the younger man's alcoholism) and his desire to rejoin

his wife Abigail, who had left for Massachusetts months before the

inauguration. Adams resumed farming at his home,

Peacefield,

in the town of Quincy (formerly a part of the town of Braintree, as it

was earlier in his life).

He began to work on an autobiography (which he

never finished), and resumed correspondence with such old friends as

Benjamin Waterhouse and

Benjamin Rush. He also began a bitter and resentful correspondence with an old family friend,

Mercy Otis Warren,

protesting how in her 1805 history of the American Revolution she had,

in his view, caricatured his political beliefs and misrepresented his

services to the country. Primarily, this revolved around a dispute about

whether Adams was sufficiently republican in Warren's view, instead of

monarchical, and was related to the Federalist/Republican political

divide.

After Jefferson's retirement from public life in 1809 after two terms

as President, Adams became more vocal. For three years he published a

stream of letters in the

Boston Patriot newspaper,

presenting a long and almost line-by-line refutation of an 1800

pamphlet by Hamilton attacking his conduct and character. Though

Hamilton had died in 1804 from a mortal wound sustained in his notorious

duel with

Aaron Burr, Adams felt the need to vindicate his character against the New Yorker's vehement attacks.

Correspondence with Jefferson

In early 1812, Adams reconciled with Jefferson. Their mutual friend

Benjamin Rush, a fellow signer of the

Declaration of Independence

who had been corresponding with both, encouraged each man to reach out

to the other. On New Year's Day 1812, Adams sent a brief, friendly note

to Jefferson to accompany the delivery of "two pieces of homespun," a

two-volume collection of lectures on rhetoric by

John Quincy Adams.

Jefferson replied immediately with a warm, friendly letter, and the two

men revived their friendship, which they conducted by mail. The

correspondence that they resumed in 1812 lasted the rest of their lives,

and thereafter has been hailed as one of their greatest legacies and a

monument of American literature.

John Adams was nearly 89 when, at the request of his son, John Quincy Adams, he posed a final time for

Gilbert Stuart (1823).

Their letters are rich in insight into both the period and the minds

of the two Presidents and revolutionary leaders. Their correspondence

lasted fourteen years, and consisted of 158 letters.

It was in these years that the two men discussed "natural aristocracy."

Jefferson said, "The natural aristocracy I consider as the most

precious gift of nature for the instruction, the trusts, and government

of society. And indeed it would have been inconsistent in creation to

have formed man for the social state, and not to have provided virtue

and wisdom enough to manage the concerns of society. May we not even say

that the form of government is best which provides most effectually for

a pure selection of these natural aristoi into the offices of

government?"

Adams wondered if it ever would be so clear who these people were,

"Your distinction between natural and artificial aristocracy does not

appear to me well founded. Birth and wealth are conferred on some men as

imperiously by nature, as genius, strength, or beauty. . . . When

aristocracies are established by human laws and honour, wealth, and

power are made hereditary by municipal laws and political institutions,

then I acknowledge artificial aristocracy to commence."

It would always be true, Adams argued, that fate would bestow influence

on some men for reasons other than true wisdom and virtue. That being

the way of nature, he thought such "talents" were natural. A good

government, therefore, had to account for that reality.

Family life

Sixteen months before John Adams' death, his son,

John Quincy Adams, became the sixth President of the United States (1825–1829), the only son of a former President to hold the office until

George W. Bush in 2001.

Adams' daughter

Abigail ("Nabby") was married to

Representative William Stephens Smith,

but she returned to her parents' home after the failure of her

marriage. She died of breast cancer in 1813. His son Charles died as an

alcoholic in 1800. Abigail, his wife, died of

typhoid

on October 28, 1818. His son Thomas and his family lived with Adams and

Louisa Smith (Abigail's niece by her brother William) to the end of

Adams' life.

[99]

Death

Less than a month before his death, John Adams issued a statement

about the destiny of the United States, which historians such as

Joy Hakim have characterized as a "warning" for his fellow citizens. Adams said:

My best wishes, in the joys, and festivities, and the solemn services

of that day on which will be completed the fiftieth year from its

birth, of the independence of the United States: a memorable epoch in

the annals of the human race, destined in future history to form the

brightest or the blackest page, according to the use or the abuse of

those political institutions by which they shall, in time to come, be

shaped by the human mind.

On July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of the

Declaration of Independence, Adams died at his home in Quincy. Told that

it was the Fourth, he answered clearly, "It is a great day. It is a

good

day." His last words have been reported as "Thomas Jefferson survives"

(Jefferson himself, however, had died hours before he did). His death

left

Charles Carroll of Carrollton as the last surviving signatory of the Declaration of Independence. John Adams died while his son

John Quincy Adams was president.

His crypt lies at

United First Parish Church (also known as the

Church of the Presidents) in Quincy. Originally, he was buried in

Hancock Cemetery, across the road from the Church. Until his record was broken by

Ronald Reagan in 2001, he was the nation's longest-living President (90 years, 247 days) maintaining that record for 175 years.

Religious views

Adams was raised a

Congregationalist,

since his ancestors were puritans. According to his biographer David

McCullough, "as his family and friends knew, Adams was both a devout

Christian, and an independent thinker".

In a letter to Benjamin Rush, Adams credited religion with the success

of his ancestors since their migration to the New World in the 1630s. Adams was educated at Harvard when the influence of

deism was growing there, and sometimes used deistic terms in his speeches and writing.

He also believed that regular church service was beneficial to man's

moral sense. Everett (1966) concludes that "Adams strove for a religion

based on a common sense sort of reasonableness" and maintained that

religion must change and evolve toward perfection.

Fielding (1940) argues that Adams' beliefs synthesized Puritan, deist, and

humanist concepts. Adams at one point said that Christianity had originally been

revelatory, but was being misinterpreted and misused in the service of superstition, fraud, and unscrupulous power.

Goff (1993) acknowledges Fielding's "persuasive argument that Adams

never was a deist because he allowed the suspension of the laws of

nature and believed that evil was internal, not the result of external

institutions."

Frazer (2004) notes that, while Adams shared many perspectives with

deists, "Adams clearly was not a deist. Deism rejected any and all

supernatural activity and intervention by God; consequently, deists did

not believe in miracles or God's providence....Adams, however, did

believe in miracles, providence, and, to a certain extent, the Bible as

revelation."

Fraser argues that Adams' "theistic rationalism, like that of the other

Founders, was a sort of middle ground between Protestantism and deism."

By contrast, David L. Holmes has argued that John Adams, beginning as a

Congregationalist, ended his days as a Christian Unitarian, accepting

central tenets of the Unitarian creed but also accepting Jesus as the

redeemer of humanity and the biblical account of his miracles as true.

In common with many of his Protestant contemporaries, Adams criticized

the claims to universal authority made by the Roman Catholic Church. In 1796, Adams denounced political opponent

Thomas Paine's criticisms of Christianity in his Deist book

The Age of Reason,

saying, "The Christian religion is, above all the religions that ever

prevailed or existed in ancient or modern times, the religion of wisdom,

virtue, equity and humanity, let the Blackguard Paine say what he

will."

Biographies

The first notable biography of John Adams appeared as the first two volumes of

The Works of John Adams, Esq., Second President of the United States,

edited by Charles Francis Adams and published between 1850 and 1856 by

Charles C. Little and James Brown in Boston. This biography's first

seven chapters were the work of

John Quincy Adams, but the rest of the biography was the work of

Charles Francis Adams.

The first modern biography was

Honest John Adams, a 1933

biography by the noted French specialist in American history Gilbert

Chinard, who came to Adams after writing his acclaimed 1929 biography of

Thomas Jefferson.

For a generation, Chinard's work was regarded as the best life of

Adams, and it is still a key factor in determining the themes of Adams

biographical and historical scholarship. Following the opening of the

Adams family papers in the 1950s,

Page Smith published the first major biography to use these previously inaccessible primary sources; his biography won a 1962

Bancroft Prize but was criticized for its scanting of Adams' intellectual life and its diffuseness. In 1975,

Peter Shaw published

The Character of John Adams, a thematic biography noted for its graceful prose and its psychological insight into Adams' life. The 1992 character study by

Joseph J. Ellis,

Passionate Sage: The Character and Legacy of John Adams,

was Ellis's first major publishing success and remains one of the most

useful and insightful studies of Adams' personality. In 1993, the

Revolutionary War historian and biographer

John E. Ferling published his acclaimed

John Adams, also noted for its psychological sensitivity; many scholars regard it as the best biography to date.

In 2001, the popular historian

David McCullough

published a large biography of John Adams that won various awards and

general acclaim. McCullough's biography was developed into a 2008

TV miniseries, in which

Paul Giamatti portrayed John Adams. Finance writer

James Grant published

John Adams, Party of One in 2005.